Dr Erica Mayer is the Director of Clinical Research and Institute Physician at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute, and Associate Professor in Medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston, in the United States.

Dr Mayer’s research focuses on the role of novel therapies in the treatment of breast cancer, and we spoke with her about her presentation at the Breast Cancer Trials 45th Annual Scientific Meeting on improving efficacy in the adjuvant treatment of early ER-positive breast cancer.

“I’m going to be speaking about ways to improve treatment for early breast cancer patients treated in the adjuvant setting, which means after surgery. There have been a lot of great advances over the past several years in how we can use different therapies to improve outcomes for patients.”

“So, we’re going to cover a variety of new strategies and how we can pick the right therapies for the right patients.”

What are the current standard treatments used in adjuvant therapy?

“For patients who have early-stage hormone-receptor positive breast cancer, a fundamental part of treatment is adjuvant endocrine therapy. This means taking medicines to block our body’s own hormones from stimulating any residual cancer cells. These include oral medicines such as tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors, and importantly for our younger patients, this might include taking medicines to purposefully put someone into menopausal state.”

“And so nowadays, that’s all a very fundamental part of treatment. Much of the work that’s being done is learning how we can add on top of that to improve how people recover. Adjuvant systemic therapy is designed to travel throughout the entire body and if there are hidden cancer cells cancer cells that have been left behind after initial treatment with surgery and radiation, the systemic therapy is designed to find those cells and try to kill them, so they never come back.”

“The primary modality that we use for hormone-receptor positive disease is adjuvant endocrine therapy, so taking medicines that block our body’s hormones from stimulating cancer cells. Some patients may also receive chemotherapy, although not everybody, and we’re very careful when we make those decisions about which patients are best suited for chemotherapy.”

Listen to the Podcast

We spoke to Dr Erica Mayer about improving efficacy in the adjuvant treatment of early ER-positive breast cancer.

What are the challenges or considerations when determining the best adjuvant treatment plan for a patient?

“When we think about what types of treatments to offer for patients, we want to consider a variety of factors. We want to think about the cancer stage, meaning how large is the cancer, has it gotten into lymph nodes? We want to think about the tumour biology, and that includes the hormone-receptor status, and the grade of the cancer. We also want to think about what’s driving the cancer cell, and what’s making it grow? And then the third feature we want to think about is, who is the person with breast cancer? What’s their health like? Do they have other competing health issues?”

“It’s also really important for us to consider someone’s personal preferences. What do they want to receive in terms of their treatment? And this is the work that the breast cancer specialist does with the patient to help come up with a personalised treatment plan. So I’m really excited to speak at this meeting about some of the new therapies that we have available for hormone-receptor positive disease.”

“One of the most important factors is a category of medicines called CDK4/6 inhibitors. These are pill medicines that are a targeted therapy. They’re not chemotherapy, they’re not hormones, but they’re their own special category. And they are designed to be used in combination with hormone medicines to help them perform better.”

“These are medicines that we use quite frequently if patients have recurrent metastatic breast cancer, and the idea is to use them earlier on in treatment to help prevent cancer from coming back and help cure a patient of breast cancer. Currently, there is one medicine that’s been approved in the United States called Abemaciclib, which is in frequent use for high-risk node-positive, hormone receptor-positive disease.”

“And there’s been a lot of research looking at other agents, which may also have benefit in this setting. So, I’m excited to cover this topic and talk about new directions for research in this area.”

“Another topic we’re going to talk about is the use of immunotherapy for hormone-receptor positive disease. This is a very specialised kind of medicine designed to stimulate our body’s own immune system to help fight the breast cancer. And we use this quite frequently for patients who have a different kind of breast cancer called triple-negative breast cancer, and we give this before surgery.”

“There’s been some very provocative data coming out in the past year looking at trying this strategy for hormone-receptor positive. And we’re going to think about how this might work and who this might be best for. And then a couple other topics we’re going to talk about are kind of emerging topics.”

“One of them is the idea of something called CTDNA. This means we can take a tube of blood from a breast cancer patient and in that tube find microscopic amounts of tumour DNA. And we can do this for people after surgery to try to establish how much risk they might be of the cancer coming back.”

“This is something we do in a research setting and we’ve seen now some recent demonstrations of how this might be helpful to establish what is a patient’s risk. But I think what we really need to figure out is if we find someone who’s at more risk than we initially thought, what do we do about it? What’s the treatment strategy? So, I want to think together about that.”

“And finally, we’re going to cover a very new emerging topic of a new kind of hormone medicine called oral SIRDS. And these are brand new medicines, mostly being studied in trials right now for metastatic breast cancer, but there are many large trials going on in the adjuvant setting that are beginning to explore these drugs potentially as a replacement for the kind of historic hormone medicines that we’ve had.”

“So, a lot of research, a lot of new discoveries. I think it’s going to really revolutionise how we take care of patients in this space. So, one thing I’ve been really impressed with working with the Breast Cancer Trials group is how much research is going on looking into the experience of patients receiving therapies in the adjuvant setting.”

“In particular, not just picking the most effective therapies and what’s going to help a patient the most but understanding the patient experience and how we can improve that, so patients are living long and healthy lives afterwards. For example, there’s great interest in how we take care of our very youngest patients, the young women who are affected by breast cancer at a time in their life when they might be starting their family or starting their career, and how can we help provide the best treatments while also maintaining things like fertility and allowing patients to have families after their initial breast cancer treatment.”

“We are also asking the question how we can best manage the symptoms that come up from some of the treatments that we offer. And I’m really excited to see how much focus is going on within the Breast Cancer Trials group, looking at answering these very important questions and really trying to optimise care in all perspectives and facets for young patients.”

How can patients make more informed decisions about their treatment?

“So, I think for someone who’s been diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer, one of the most important things first is having a good relationship with your providers. Breast cancer teams around the world are so highly trained, and we work together as a global community to provide the best possible care for patients.”

“And so being comfortable asking questions, and you know, if you hear about something or read about something, bring it up with your provider. See what they think, bounce it off them. I think that’s really important. Also, none of the work we have available today, none of the important tools would exist without patients volunteering to be part of clinical trials.”

“Participating in trials is an immensely important way to help move the needle forward with how we take care of breast cancer patients. There are so many trials available around the world. Many of the most important trials going on are available to patients in Australia and New Zealand. And it would be so important for people to ask your provider, can I be in a trial? Am I eligible for a trial? What trials do you have going on right now?”

“These decisions that we make on an individual basis will have ramifications for patients around the world as we learn the results of these trials and we can optimise therapies. So, I really encourage people to ask about being part of research.”

What role does a patient’s hormone-receptor status play in the treatment of their breast cancer?

“When a patient is first diagnosed with breast cancer, it’s important to learn as much as we can about the cancer in order to optimize therapy. There are three major categories of breast cancer that somebody can have, and that’s defined by receptors that we test on the outside of the cancer cell.”

“There are the hormone receptors, there’s HER2-receptors, and then there’s also cancers that do not test for any of these receptors. Those are called triple-negative breast cancers. Learning which variety or subtype of breast cancer a patient has is one of the first steps that we have in understanding what are we dealing with and also beginning to think about how to pick all the best strategies.”

“Most breast cancer is hormone-receptor positive, HER2-negative. That’s about two thirds of all breast cancer. And that’s an area where there’s been a tremendous research focus on trying to provide really good therapies that help to optimally kill cancer cells but not expose somebody to too much treatment or too much toxicity that’s not going to be helpful.”

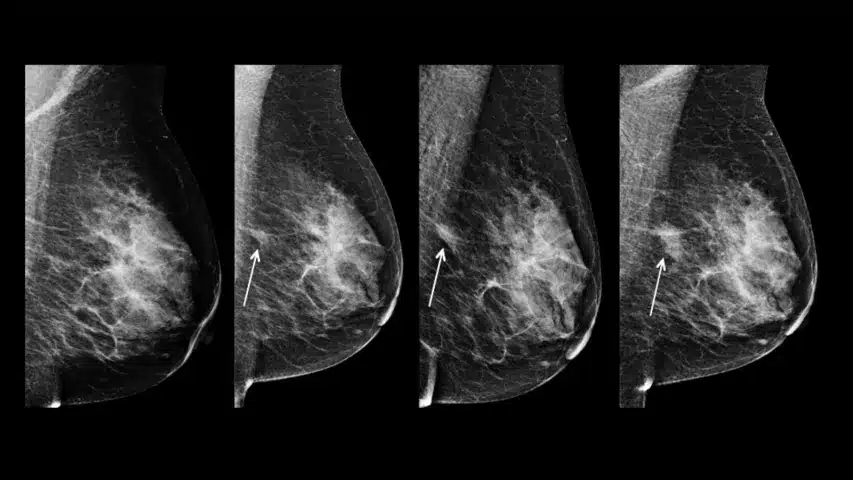

“I’d say one of the most exciting things that’s happened in the world of hormone receptor positive early breast cancer over the past couple of decades has been the use of genomic tools. We have a test called Oncotype, which is a test done on tumour tissue that’s removed either with biopsy or a time of surgery.”

“This test is really important because not only does it give us a little insight into the breast cancer tumour biology, but it also teaches us about whether a cancer is sensitive or not sensitive to chemotherapy. Not every cancer responds to chemotherapy. Not every cancer is sensitive. And we certainly don’t want to give that to somebody if it’s not going to help them.”

“And so, for the vast majority of people who are diagnosed with hormone receptor positive breast cancer, we do send these types of tests. And this really helps us better understand and select who the people are, in which chemotherapy will be helpful, and they should go for it. And then who doesn’t need it? Who can be spared that exposure?”

“We want to offer the right therapy for the right patient, and tests like Oncotype have helped us get there.”

How important is international collaboration in breast cancer trials?

“I’m so delighted to be here in Australia meeting with my colleagues from around the world and in particular my very dear colleagues from Breast Cancer Trials.”

“The breast cancer community is a very tight global community. We come together for our meetings, which occur throughout the globe. And we meet frequently to design trials and lead trials and talk about patients. And in no way do we do this in isolation, we all work together. It’s incredibly gratifying to meet with my colleagues who work in places all over the world and find that our treatment patterns and our treatment decisions are very consistent.”

“The way we take care of breast cancer in Sydney is very similar to how we take care of breast cancer in Boston, or Vienna, or London, or anywhere. And so, this is very helpful because this means that we can run global clinical trials. Knowing that we can improve the standard of care in all of these places around the world.”

“So, it’s really exciting to be part of such a tight knit global community. And I think that also provides a lot of confidence for patients. That no matter where you are in the world, your doctors talk to other doctors in other countries, they attend international meetings, and the decisions that are made are decisions that are not specific to your clinic or your country, but these are the decisions that people around the world are making together.”

“So, I’m very much reminded of that when I come to visit with my colleagues, and I’m really just gratified for our international community.”