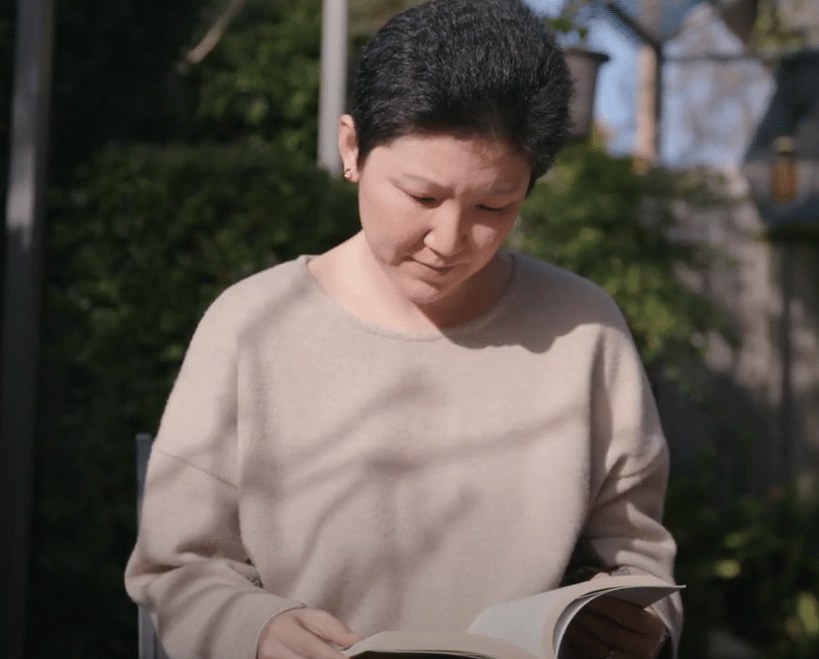

Being Diagnosed with Breast Cancer

Jan White is a 75-year-old retired nurse who used to work in health, disability and aged care. Since she can remember, Jan has been having two yearly mammograms, and like any other appointment, she went in asymptomatic and expecting the ‘all clear’. However, the mammogram displayed a lump in her breast and she was diagnosed with breast cancer.

Jan is a participant in the EXPERT clinical trial, which aims to improve personalised use of radiation therapy in early breast cancer patients. We spoke with Jan about her diagnosis and her decision to participate in a clinical trial.

“My breast cancer diagnosis came about because even at my age I was still undertaking two yearly mammograms, which was my choice, and I went for one of my due mammograms, had no symptoms whatsoever and even after the mammogram none of the surgeons or nurses or anybody could feel the lump. So, without the mammogram it would have been undiagnosed.”

“So, I was lucky that I had continued going in for my mammograms, because in New Zealand we have to pay privately for them at my age, and otherwise I wouldn’t have been diagnosed. And because of that mammogram the tumor got picked up really early, which meant my risks were also reduced significantly, it turns out.”

“It was definitely a real surprise to me, not at all what I expected. I usually, like most women do, trot into our mammograms thinking, ‘oh yeah, I’ll have it done, so what?’ And then out came that diagnosis. I did have an inkling at the mammogram because the woman who was doing it went away to talk to a radiographer and then came back and wanted to take different shots.”

“So, because of my clinical background, I thought that something must be going on. But it was a shock, and something that I guess we all react to differently. I have a fairly ‘get on with it’ attitude to life, so did just get on with it. My husband doesn’t react very well to clinical things, so I almost brushed it over for him.”

“So, I was essentially managing it on my own, because I’d also made the decision that we wouldn’t involve family until I knew if I was having surgery, because I hadn’t seen a surgeon at that stage. But it turned out that we did tell our daughter and she came with me to the initial appointment with the surgeon and so they were all of course very supportive.”

“The boys we told what I was having the surgery for and that we were pretty sure it was early, and that there was no point flying into a blind panic about anything until we knew what the journey was going to be. And we decided not to tell the grandchildren despite their age, we just told them that Grandma was having some surgery, because three out of the four were all sitting exams at university and I didn’t want them getting emotionally upset about me and not doing well on their exams essentially.”

“Yeah, so since they found out they’ve all been fine, they’ve all adopted my attitude. I’ve been the strong one in the family, so I have always been inclined to brush over my own needs, which I continue to do with this. So I don’t think particularly the grandchildren realise the impact that this has had on me because I’ve hidden it from them, although the granddaughters might have picked up on it.”

Listen to the Podcast

Jan is a participant in the EXPERT clinical trial, which aims to improve personalised use of radiation therapy in early breast cancer patients. We spoke with Jan about her diagnosis and her decision to participate in a clinical trial.

How did you find out about the EXPERT Clinical Trial?

“When I came to my surgeon for the follow up after my surgery and to get the pathology reports, he went through all the pathology report with me and explained it all and, and that he felt that I was really lucky, the tumor was caught really early and I was really low risk. The biopsy came up with no spread, and he felt that it was a very early tumor.”

“He didn’t mention having radiotherapy to me and I remember sitting there thinking that he discussed radiotherapy at the initial appointment and so I asked him. So, he explained further about the level of risk that he thought I was and that he felt that it could be my decision whether I had radiotherapy or not and to go away and think about that. And I said, I can’t make that decision because everything I’ve been taught tells me to have radiotherapy, but the common sense of what I’m hearing tells me I don’t need it.”

“And he looked at me and he said, well I can’t tell you what to do Jan, I can only give you the information. And so, I said I’ll go and think about it. And as I went to leave, he said to me that there was this trial that I could participate in. Although I wasn’t compelled to, and then handed me over all the information, which is a huge amount of information, I think it’s about 15 pages.”

“So, he went through it briefly with me and said to go home, have a read, and think about it. And to let him know if I wanted to think about participating in the EXPERT trial, or if I wanted to do the radiotherapy or not. So, I went with the trial.”

“And he was very clear that even if I decided to go on the trial, and then decided partway through it that I was going to do radiotherapy, or if I was randomized not to have the new treatment, that I could pull out at any time. And that was big for me, knowing that I could decide this, but partway through if I really felt I needed to, I could pull out.”

“So, I went home, read all the information, and me being me, I researched the tests that the trial tells you that are undertaken in laboratories, and said yes. The reason for that is because thinking about it I decided I’d trust the science because I actually couldn’t make the decision on my own because of all my background and all my training. So, I decided that I would participate in the trial and trust the science and if I was randomised and didn’t have radiotherapy, that I would go with what the science was telling us for the trial.”

“I’m very committed to other people and my community. So the more I thought about it, the more I thought that if the science tells me I am low risk and can be randomised, that I actually owed it to future generations, and particularly older woman, to participate in the trial, which I understood would help guide whether, in fact, we needed essentially to have radiotherapy or not, when certain criteria are met with breast cancer.”

What has been involved in your treatment?

“It’s actually been really easy. There was another appointment with Dr Campbell, who happens to be the lead researcher, but also my surgeon. And appointments with Jenny, my research nurse. They went through line by line, all that information about the trial and the risks to me based on my pathology, and more importantly the ability to withdraw at any time.”

“They explained that if you scored under, I think it was 60. That neither they or I would know whether it was 60 or 15. So we wouldn’t know the percentage of risk for want of a better word. Just that it was deemed in the low-risk category, and I was therefore eligible for the trial. They also explained that if I was randomised, for the current standard of treatment that I would have radiotherapy plus the exemestane that Dr Campbell had prescribed.”

“And if I was randomised without traditional therapy then I would just have the tablets. And I was randomised without. So, I’m quite comfortable now with the decision I have made to trust the trial and trust the science. I’ve only been in the trial coming up to three months, so I’m about to have my first follow up.”

“And that was another thing that my daughter pointed out. She said to me that if I did go on the trial, I would have three monthly checkups for the next five years, including follow up with a nurse, and, you know, that’s just extra checking. So, breast exams and annual mammograms, and we have to have them anyway, but the trial will make sure I’m having it done regularly and having regular blood tests, checking bone density and all those sorts of things. They all get covered off nicely by someone else managing it, which will be nice.”

“So, I think that’s another bonus of the trial for women. Is that we get that extra follow up, that extra back up plan, those extra people that we can talk to if we need to. I think it’s important.”

“I’ve both nursed people, and I have friends and colleagues and I volunteer up at the Cancer Lodge here, so I see and have heard about some of the effects of radiotherapy. Not all women have side effects, like anything. Some of us get them, some of us don’t. But particularly older women appear to maybe have more side effects, or perhaps, if not side effects, have a greater impact on their lives from radiotherapy.”

“So, if they don’t need to go through that, and research can guide us on that, because you can’t just make the decision and pull it out of the air. It’s got to be research based; I think then that’s why we should do the trial.”

“If you’ve got the ability to support donating to any sort of research, but in this case, breast cancer, absolutely do it. I do a lot of talking in my big networks to people about the importance of donating to research and clinical trials and support research groups. So absolutely. If somebody asked me if I had somewhere they could suggest that they’d donate to, breast cancer research is on the list.”

What Would you say to Someone who was Thinking About Participating in a Clinical Trial?

“Absolutely do it, and I absolutely recommend it if you’ve weighed up the risks, you’ve been told all the information as I was. Absolutely. There’s lots of diseases that have been cured or managed because of research and people doing what the trial is doing.”

“It makes me feel good knowing that I might be helping future generations through participating in this research. It makes me feel as if my diagnosis has got some good out of it, if the trials and the research are able to alter the management of breast cancer, which is important for women. I mean even 10 or 15 years ago, women were dying of breast cancer. We’re often not now.”