How Does Breast Cancer Metastasise?

Metastatic breast cancer occurs when cancer cells break away from the cancer in the breast and move through the blood vessels or lymphatic vessels and form a new cancer growth in other parts of the body.

If breast cancer has spread and metastasised, it is still considered breast cancer and will be treated as such. This is because the cells which have spread are breast cancer cells. For example, if breast cancer has spread to the liver, the metastatic tumour in the liver is made up of breast cancer cells, not liver cells.

What Are the Symptoms of Metastatic Breast Cancer?

Metastatic breast cancer most commonly appears in the liver, brain, bones, or lungs (but can also occur in other parts of the body). Depending on where the cancer has spread, the following symptoms may be present. However, metastatic breast cancer can present in many different ways and if you have metastatic breast cancer, you may not present with any symptoms.

It is also important to note that some of these symptoms may not be due to metastatic breast cancer.

Bone metastasis: If breast cancer has spread to the bones, the most common symptom is a new pain or ache in the bone. Breast cancer can spread to any bone but is most commonly found in the ribs, spine, pelvis, arms, or legs.

Brain metastasis: If breast cancer has spread to the brain, you may have headaches, nausea, vomiting, vision or speech changes or memory problems. In some rare cases, symptoms can include seizures, confusion, or a change in personality.

Liver metastasis: If breast cancer has spread to the liver, symptoms may include weight loss, tiredness, and discomfort on the right side of the abdomen or stomach where the liver is located. Other less common symptoms include nausea, loss of appetite, jaundice and swelling of the abdomen.

Lung metastasis: Most commonly, the first symptom that breast cancer has spread to the lungs is a shortness of breath or a dry cough. Other less common symptoms include chest pain or a feeling of heaviness in the chest. However, it is common for breast cancer which has spread to the lung or lungs to present with no symptoms.

If you notice any of these symptoms, it is important not to panic as this may not mean your breast cancer has spread.

Consult with your doctor if you have any concerns regarding your health.

How is Metastatic Breast Cancer Diagnosed?

If your doctor suspects your breast cancer has metastasised, they will organise specific tests dependent on where they believe the cancer has spread.

To diagnose bone metastases: Bone scan, Xray, CT scan, MRI, PET scan and/or blood test.

To diagnose lung metastases: Examination of mucus under microscope, bronchoscopy, lung needle biopsy and/or surgery.

To diagnose brain metastases: MRI – often with contrast solution and a biopsy may be necessary in rare occasions.

To diagnose liver metastases: Liver function tests, MRI, CT scan, ultrasound, PET scan and/or biopsy.

How Is Metastatic Breast Cancer Treated?

Every metastatic breast cancer diagnosis is different and will therefore require different treatments. Despite the cancer growths being in other organs, such as the lung, it is called ‘breast cancer’ and is treated as breast cancer.

The aim of treating metastatic breast cancer is to control the growth and spread of the cancer, to relieve symptoms and improve or maintain quality of life.

Treatment options will depend on what is most likely to control the cancer and what side effects the patient can cope with. Treatment for metastatic breast cancer can include hormonal therapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, radiotherapy, and surgery.

Why Is Metastatic Breast Cancer Difficult to Treat?

There are a number of reasons why metastatic breast cancer is difficult to treat.

One reason is that many who are diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer have already been exposed to therapeutic drug treatments and the cancer has therefore have already had an opportunity to acquire some resistance. Another reason is that there is less of an opportunity to remove the cancer surgically, as the cancer has spread and become larger than it was in the primary site. Surgery is typically not used for metastatic breast cancer, apart from highly selected cases. There may also be additional genetic events that have occurred during the course the disease which, over the period of time while the cancer is regrowing, have made them more resistant to therapies.

Researchers are working to better understand why breast cancer metastasises, so they can create new and better targeted treatments.

Are There Different Kinds of Metastatic Breast Cancer?

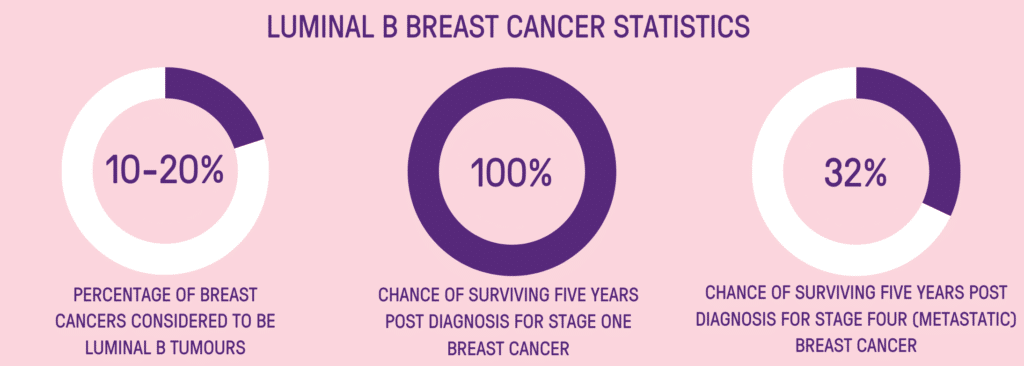

Yes. Metastatic breast cancer means the disease has spread from the original breast cancer site located in the breast. It means it has spread to other organs in the body, most commonly the bones, liver, lungs, or brain. Metastatic breast cancer can be one of four different molecular subtypes; Luminal A (Hormone Receptor Positive HER2 Negative (HR+/HER2-) Breast Cancer), Luminal B (High grade, Hormone Receptor Positive, HER2 positive or negative (HR+/HER2+) Breast Cancer), HER2 positive breast cancer or triple negative breast cancer. The subtype of breast cancer, and the location it has metastasised will determine how the cancer is treated.

How Common is Metastatic Breast Cancer?

According to the latest data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, approximately 4.6% of breast cancers diagnosed each year in Australia are stage 4. New Zealand’s incidence rates are similar.

What Are My Chances of Survival (Prognosis) If I Am Diagnosed with Metastatic Breast Cancer?

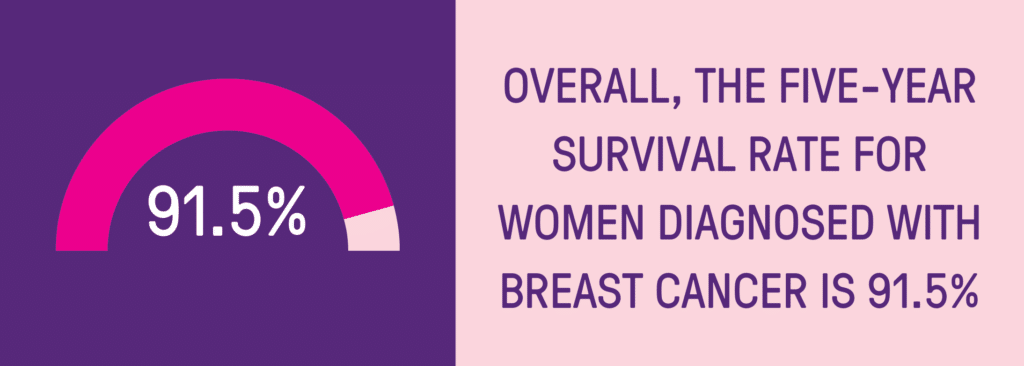

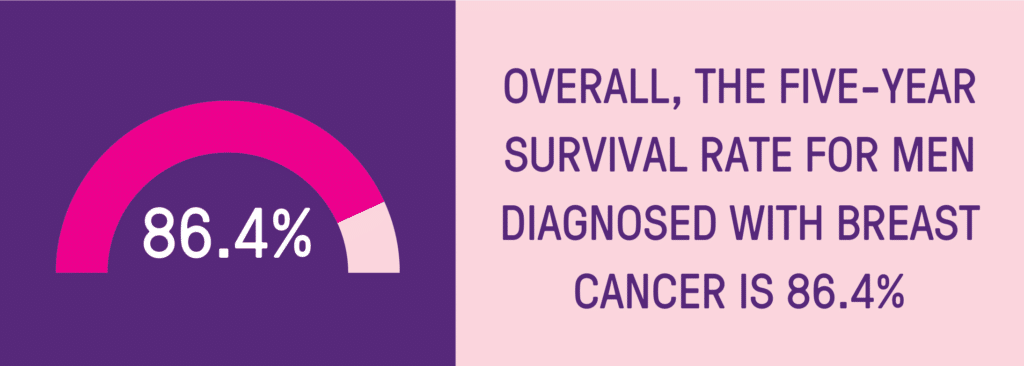

Breast cancer survival is measured in 5-year relative survival. This means how many people diagnosed with breast cancer are still alive five years after their initial diagnosis.

According to the latest data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, the five-year relative survival for those diagnosed with stage 4 breast cancer is 32%. The survival rates in New Zealand are similar. This means 32% of people diagnosed with stage 4 breast cancer are alive 5 years after their diagnosis.

However, these statistics can’t predict your personal breast cancer prognosis. Breast cancer survival differs and there are many factors that can influence this such as your response to treatment, the type of breast cancer you have, medical history, overall health, age, and tumour growth. You should discuss your personal situation with your doctor and/or treatment team.

Is Metastatic Breast Cancer ‘Curable’?

Currently there is no cure for metastatic breast cancer. However new and better treatment options mean that the cancer can remain under control for longer, sometimes for years at time.

Those diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer will need to undergo treatment for the rest of their lives. If one treatment ceases to be effective in keeping the cancer under control, another treatment regime may be suggested. These treatments are generally given for as long as they are providing a benefit to the patient. The goal is to maintain the best quality of life achievable, and to prolong life if possible.

Every diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer is different, and therefore each treatment regime and prognosis will be different. Your doctor and/or treatment team are best to advise on your personal medical situation.

Support Us

Help us to change lives through breast cancer clinical trials research