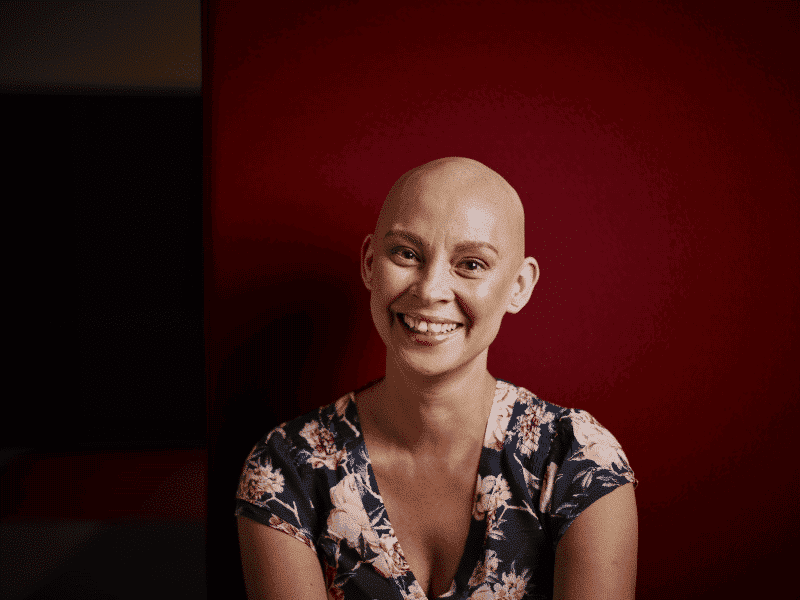

Heidi’s Story

It’s recommended that women in Australia start getting routine mammograms at the age of 50.

43-year-old Heidi Routley started early after a push from a friend who was diagnosed in her early 40s.

She is thankful she did after the breast cancer subtype Invasive Ductal Carcinoma was discovered in a routine mammogram, one year after she started scheduling them for herself.

“A friend of ours was diagnosed at around 43/44 and she asked everyone that she knew to go and get a mammogram at the age of 40,” she said.

“I was a little bit late getting it done, with life, with children and studying a masters, and so then I went and got one done when I was 42.”

Heidi was on her third mammogram when a calcification was found.

“So, I had to have a biopsy.”

“I thought it would be nothing. Turned out that it wasn’t nothing.”

She said the push from her friend saved her life.

“So, ultimately our friend going through that has saved my life and now it’s saved another life as me going out there and telling my friends, ‘get a mammogram’, another friend of a friend has just had a DCIS found.”

“It seems to be this continual line where people are finding out but it’s about knowing and being aware of it and getting it before it’s too late.”

Listen to the podcast

Heidi tells us what it’s like being diagnosed as a young woman with a young family, having to put your career on hold and not being afraid to ask for help when you need it.

Receiving The Diagnosis

Heidi wasn’t expecting the biopsy to result in a diagnosis.

“I was standing in Coles buying a birthday cake for my mum for dinner that night and my phone rang.”

“It was my surgeon. He rang to tell me that it was breast cancer.”

“The first thing I did was I went and sat outside of Coles and I rang my university lecturer because I was just finishing my masters and I had my final assignment due on the Sunday and that was the Wednesday.”

“I rang her straight away and I said I just don’t know how I’m going to get this assignment done and told her what was going on.”

“She said ‘it doesn’t matter Heidi, It’s a piece of paper. We’ll get that done. You look after yourself.’”

“I also got my accreditation from the NSW Department of Education that day to say that I was able to teach, so it was a bittersweet moment.”

“I had been waiting for this piece of paper to come through, to say that I can teach now and then all of a sudden, it’s taken away, because I haven’t actually taught yet since I’ve been diagnosed because I’ve just been too ill to do so.”

“Getting that piece of paper but getting that diagnosis on the same day, and on my mum’s birthday, was pretty daunting,” she said.

She said undergoing treatment at a point in her life where she expected to begin a new career was challenging.

“My oncologist didn’t want me to be teaching, especially during that first chemo.”

“It’s been really hard considering we’d budgeted over the past 3 and a half years for me to study. We knew that there was a bit of an end period coming up and I’d be able to start working again.”

“So, we were treading water a bit financially.”

Reaching Out And Accepting Support

Heidi said the support she received from family and external charitable organisations has helped enormously.

“I’ve got my amazing family and friends and they’ve organised a food train, so we’ve got meals coming on chemo weeks so that it’s not so much pressure on my husband to sort dinner out for us.”

“Everyone has come together and it’s been amazing helping me through it.”

“But there are also so many great organisations out there who have helped financially, just with cleaning and things like that.”

“I’ve used Mummy’s Wish, which is an organisations for mums with cancer and they’ve organised a beautiful teddy bear for my son, which has got a little love heart voice recorder so you can record messages if you’re going in and out of hospital.”

“They’ve also organised house cleaning for us.”

“There is also the OTIS foundation which is a foundation where they will provide holidays for families with cancer, so I’ve put my name down for that as well. And also the Hunter Breast Cancer Foundation, they’ll be doing some cleaning and they’ve got the wig library as well.”

“So, there’s lots of different things out there but you just have to swallow your pride a little bit and take use of those organisations.”

Heidi said her advice is to accept the help and support offered.

“It’s really hard to say yes, I need help, but people want to help you,” she said.

“If people say, ‘what can we do for you’ they genuinely mean it.”

She also encourages young women to be proactive about their health.

“Get that mammogram, make sure your friends are getting them.”

“If you feel something, and it doesn’t feel like it’s right, don’t let the doctors tell you that it’s just a cyst or something, get a second opinion.”

“It’s your body, you need to take charge of it.”

Why I Support Breast Cancer Trials

Heidi is a supporter of Breast Cancer Trials and has recently participated in a Breast Cancer Trials awareness campaign.

“For me particularly, because I’m triple negative breast cancer, that means that the likelihood of my re-occurrence is higher than normal breast cancer, that’s hormone related.”

“Which I didn’t know when I first got diagnosed.”

“I thought ‘oh yay, I’m triple negative – negative is a good thing’, but then I did some research and it wasn’t such a good thing.”

“So, for me, in Breast Cancer Trials research, if there’s something there that can pick up on those tumour cells earlier, especially for triple negative breast cancer for patients like me – then it’s all worth it.”

Support Us

Help us to change lives through breast cancer clinical trials research