When someone is diagnosed with breast cancer, the focus goes beyond treating the disease itself. Supportive care plays an important role in looking after a patient’s physical, emotional, and mental wellbeing. It helps to manage symptoms, ease the side effects of treatment, and improve comfort throughout their treatment and recovery.

What’s the meaning of supportive care?

Supportive care refers to treatments and support that focus on improving an individual’s quality of life while they’re receiving care for breast cancer and after their treatment is complete.

What is often included in supportive care?

- Help managing side effects like pain, nausea, or fatigue

- Counselling and emotional support

- Nutritional guidance and physical therapy

- Support with hot flashes, hair loss, or body image changes

Breast Cancer Trials has conducted several clinical trials that have helped transform support to patients, including:

- Preserving Fertility During Breast Cancer Treatment: The POEMS trial studied the use of goserelin to protect fertility during chemotherapy. It found that women who received goserelin were less likely to experience early menopause and had a higher chance of pregnancy after treatment.

- Identifying Patients Who May Not Need Chemotherapy: The TAILORx trial showed that many women with hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative, early-stage breast cancer could safely avoid chemotherapy, reducing unnecessary side effects.

- Advancements in Surgery Reduction Techniques: The IBCSG-23 trial investigated whether patients with cancer in sentinel (or main) lymph nodes could avoid extensive lymph node removal. The study showed that less surgery did not affect survival and helped reduce side effects.

Breakthroughs like these are often referred to as treatment optimisation – making sure patients get the best possible outcome with the least possible side effects.

What is the role of supportive care in breast cancer?

Supportive care has become a central part of breast cancer treatment in Australia. Thanks to advances in research, survival rates for breast cancer have improved significantly over the last 30 years. During this time, research has broadened to not only include studies into improved treatments and preventions, but to also advance our knowledge in how to ensure that patients experience the best possible quality of life during and after treatment.

Clinical trials led by Breast Cancer Trials have improved supportive care by:

- Reducing side effects,

- Preserving fertility

- Helping determine which patients can avoid chemotherapy or extensive surgery

Aspects of supportive care include:

- Managing Treatment Side Effects: Addressing issues such as pain, fatigue, and nausea to help patients maintain daily activities and well-being. It can also help patients better tolerate treatment, meaning they are less likely to cease treatment

- Providing Psychological and Emotional Support: Offering counselling and support services to help patients navigate the emotional challenges of a cancer diagnosis and the effects of treatment.

- Facilitating Physical Rehabilitation: Implementing exercise and rehabilitation programs to help manage side effects, restore physical function post-treatment and optimise general health.

“What I would love is for patients to have the best possible treatment that helps them live the longest but feel the best.” — Dr Deme Karikios, Medical Oncologist, Nepean Hospital on quality of life outcomes and treatment success.

Supportive care is valuable at every stage of breast cancer, including:

- At diagnosis: Offering clear information, counselling, ensuring psychological support and decision-making support.

- During treamtent: Your medical team will develop a personalised treatment plan that not only includes treating your type and stage of breast cancer, but also aims to help you feel as well and function as well as possible during treatment. This includes addressing physical, psychological, emotional, social and financial effects of treatment. There are a range of support services available to patients outside of their treatment team, including:

- Online networks to speak with others going through a similar experience

- Online resources including a library of articles, personal stories, podcasts and videos.

- Resources to understand finance and practical support

- Breast cancer support and services in nearby areas

- After treatment: Assisting with rehabilitation, fear of recurrence, and ongoing wellbeing.

Symptom management: easing the burden of treatment

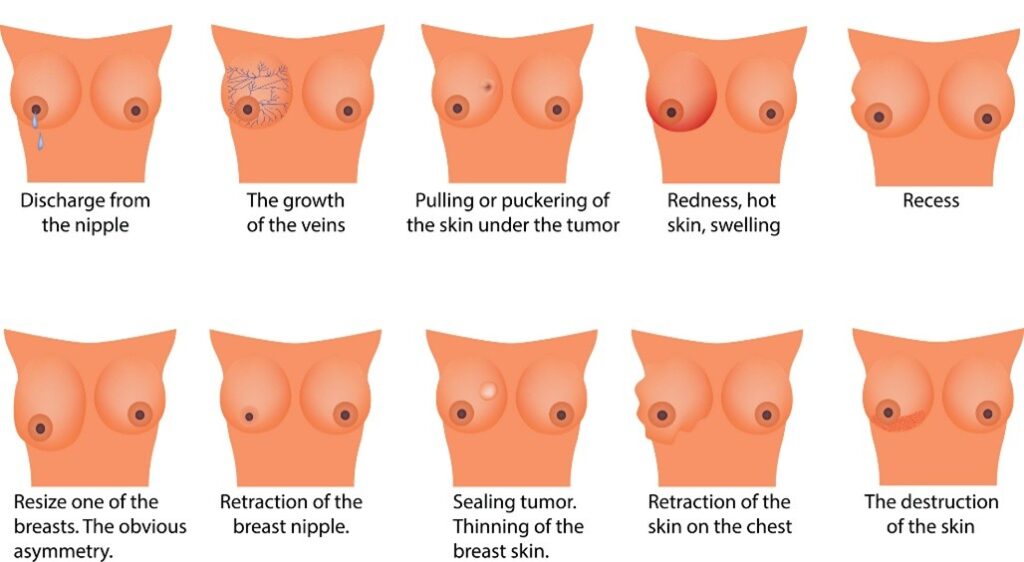

Supportive care aims to ease the physical and psychological effects of breast cancer and its treatment. These symptoms can be different for everyone. Some of the most common symptoms include:

- Pain Management: Breast cancer therapy can cause discomfort for several reasons with treatment including both non pharmacological and pharmacological strategies to address the cause of the pain.

- Nausea and fatigue management: Effectively managing nausea and fatigue can significantly improve overall well-being during treatment. Treatment related nausea predominantly occurs around the time of breast cancer treatment The PantoCIN study delivered encouraging results where Pantoprazole completely alleviated delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) in one out of eight participants, and the overall group reported reduced nausea.

- Lymphoedema: Swelling in the arms or chest can occur after lymph node removal or the lymph nodes not working properly.

- Hot flashes: Treatments that temporarily reduce oestrogen levels can trigger hot flashes. It’s also common for pre- and peri-menopausal women to enter premature menopause because of treatments like chemotherapy, which can also cause hot flashes.

Supportive treatment approaches

Supportive care utilises a holistic approach, focusing on:

- Physical recovery

- Emotional resilience

- Nutrition

- Mental well-being

These approaches make a real difference during treatment and throughout recovery.

Counselling and Psychological Support

Emotional and psychological support can be helpful during breast cancer treatment and recovery. There are various services available to assist with the mental and emotional challenges of breast cancer. For further information on resources, view our support services.

- Body image, self-esteem and intimacy: Treatment can lead to significant changes in a patient’s body, which may impact body image, self-esteem, sexuality, intimacy, and relationships. Having access to a supportive network and professional guidance can provide valuable psychological support during this time.

- Learn more about mental health, body image & breast cancer.

- Watch our Q&A Event that discusses the impact a diagnosis and subsequent treatment can have on a person’s sex life.

Psychosocial Support

- Psychosocial and peer support: Having access to a support system and being able to relate to others going through a similar experience, can help aid feelings of isolation and anxiety.

Nutritional Support

- Dietary guidance during treatment: Maintaining a balanced, nourishing diet can help support energy levels, immune function, and recovery. A dietitian can provide personalised advice to manage changes in appetite, taste, or nutrient absorption caused by treatment.

- Managing side effects related to digestion: Breast cancer treatment can cause appetite changes, constipation, or diarrhoea. Nutritional support plays a key role in addressing these symptoms, helping you stay as comfortable and well-nourished as possible throughout treatment.

- The role of diet and exercise in breast cancer care: Maintaining a balanced diet and staying active are key to managing health during and after treatment. Together, they can help reduce side effects, support recovery, and improve long-term outcomes. To learn more about their impact, watch our Q&A video on the impact of diet and exercise in breast cancer care.

Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation

- Physical exercise programs: Tailored exercise plans can help rebuild strength, improve mobility, and boost energy levels during and after treatment. Learn more about the benefits of physical exercise.

- Encouraging participation in healthy lifestyle programs: As part of the Breast Cancer Trials Clinical Fellowship Program, Dr Cindy Tan is leading a project to better understand and improve how patients engage with diet and exercise programs after early-stage breast cancer treatment. The goal is to help more patients access and stick with lifestyle changes that support long-term health. Learn more about this research.

- Rehabilitation for side effects: Physical therapy and rehabilitation play an important role in recovery following procedures like sentinel lymph node biopsy or axillary clearance than can cause side effects like cording after breast cancer. Rehabilitation can help improve shoulder and arm movement, reduce stiffness, and support the body’s healing process.

Is supportive care the same as palliative care?

This is a common question. While supportive care and palliative care both aim to improve comfort and quality of life, they are applied in different ways:

- Supportive care is useful at any stage of breast cancer, starting from the moment of diagnosis. It helps manage symptoms, support physical and emotional health, and improve overall wellbeing throughout treatment.

- Palliative care is more commonly associated with advanced or metastatic breast cancer. It focuses on easing pain and other symptoms when a cure is not possible, ensuring the patient remains as comfortable as possible. It also provides emotional and spiritual support for both the patient and their family.

Both types of care are important for managing symptoms and improving the patient’s quality of life.

The role of clinical trials in advancing supportive care

Supportive care is an important area of breast cancer research. While much of the focus is on treating the cancer itself, there is also significant research aimed at improving patients’ wellbeing and reducing the impact of treatment. Areas that are being explored or may be investigated in future research include:

- Symptom management: Investigating better ways to manage breast cancer fatigue, pain, nausea, and hot flashes, helping patients stay comfortable during treatment.

- Measuring quality of life and general well-being: Conducting trials that measure how treatment side effects, such as fertility changes and chemotherapy symptoms, affect daily life is important for understanding where there are gaps in supportive care, and how interventions can be designed to improve quality of life and general well-being.

- Genetic and personalised supportive care: Investigating how genetics impact responses to treatments, aiming to provide more tailored treatment and prevention with fewer side effects.

- The OlympiA Trial found that administering Olaparib tablets twice daily for one year, following local treatment then standard chemotherapy, improved overall survival rates in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations.

- The BRCA-P Trial is an ongoing study evaluating the effectiveness of the drug Denosumab in reducing or preventing the risk of breast cancer in women with a BRCA1 gene mutation.

Why is supportive care research so important?

Supportive care is important because it focuses on the person as a whole—not just the breast cancer. It addresses the emotional, social, and physical challenges that come with treatment and recovery.

While the primary goal of breast cancer treatment is to manage the disease, the experience of living with breast cancer is equally significant. Supportive care ensures that individuals stay well, informed, and connected throughout their journey, helping them cope with the side effects and emotional toll of treatment.

Research in supportive care is just as important as discovering new treatments for breast cancer itself, as it aims to improve quality of life and the overall experience for those affected by the disease.

Donate today to support research that enhances the quality of life for those undergoing breast cancer treatment.

Support Us

Help us to change lives through breast cancer clinical trials research